THE THAI EGGPLANT is tiny and round, dainty in the hand. The Annina eggplant hangs straight down, like a bell. The Picasso eggplant is a dark teardrop. The bulbous Tango eggplant is white on the shrub but turns butter yellow when plucked. There are eggplants that look like oversize grapes, orange softballs, red onions gone goth. More often seen in U.S. supermarkets are the Italian eggplant, deep purple and fat bottomed like a wobble doll, and the globe eggplant, the same shape but ballooned outward — known, perhaps inevitably, as the American eggplant, a skyscraper among its kind.

Still, the one that has come to rule them all is the Japanese eggplant, slender and glossy, presented at an upward tilt, a regal baton to be handed off to the next runner, with the green cap of its calyx perched perkily on top. Such is the eggplant immortalized in emoji, which in the past quarter-century has become the world’s favored shorthand, a way to both communicate and dispense with the bother of communication. The first emojis, released by the Japanese tech conglomerate SoftBank in 1997, were pixelated and black and white, and included a saxophone, a broken heart, a slice of strawberry shortcake and Mount Fuji, but no eggplant. When finally introduced in 1999 — again, only in Japan — the eggplant emoji called to mind a pudgy purple worm with its body half-lifted, as if caught mid-sun salutation, doing cobra pose. Apple’s version of the eggplant, available to Japanese iPhone users starting in 2008 and internationally across device platforms in 2012, was sleeker and firmer, and that happy-to-see-you silhouette has persisted to the present day.

Last year, the eggplant was the 165th most popular emoji (out of 1,549 measured) in the United States, and the highest ranking culinary ingredient, as reported by the Unicode Consortium, the nonprofit organization that regulates standards for digital text. In the food and beverage category, only birthday cake (No. 25), a cup of coffee (No. 124), beer steins (No. 140) and clinking champagne flutes (No. 155) surpass it. Its charms are straightforward, appealing to the eternal giggly adolescent in all of us. Somehow it never gets old, the resplendent inanity of seeing sex in erstwhile innocent, innocuous objects — as if it were always on our minds; as if we were ever on the lookout, ever wistful for some more immediate, animal life — and the serendipity of well-placed fruit, from the pineapples and melons with which the British actress Elizabeth Hurley adroitly blocks a view of her chest in the 1997 comedy “Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery” to the cucumber that the British artist Sarah Lucas stuck into a mattress so that it stands at a near vertical, looming over two oranges, in her 1994 sculpture “Au Naturel.” (You might argue that a cucumber is a vegetable, except, botanically speaking, vegetables don’t exist; both the cucumber and the eggplant are classified as berries.)

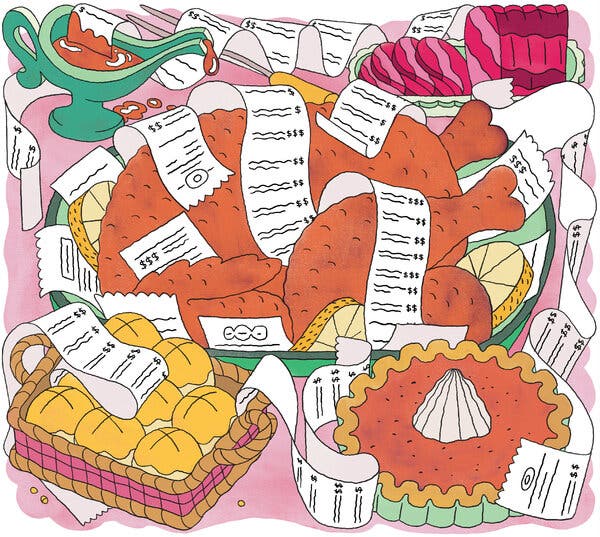

But the real-life eggplant, the one you can touch, lavish olive oil on and roast until tender and lush, remains a wallflower, ignored and underappreciated. According to U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates (extrapolated from food availability data and adjusted for spoilage and other loss), in 2020, Americans devoured more than 20 pounds of potatoes per capita but could muster the appetite for only around 6.5 ounces of eggplant. And while this represents an increase of nearly a third from the pre-emoji statistic of just under five ounces in 2010, it’s hardly proof of crossover success. Americans like to text eggplants, not actually eat them. If anything, the eggplant’s outsider status, its very lack of significance in American life, made it easier to endow with other meanings — and more of a surprise when it first popped up, ready for action, onscreen.

SOMETIMES A FRUIT is just a fruit. But since the beginning of recorded human thought, we have insisted on fruit as a sexual metaphor. “Marry me, / give me the fruit of your body!” the goddess Ishtar commands the hero in the Sumerian epic “Gilgamesh,” which was inscribed in cuneiform, the earliest known writing system, on a baked clay tablet nearly 4,000 years ago. In Genesis, Eve takes a bite of “p’ri,” Hebrew for “fruit” — of any kind: The specification of the apple was a later Latin pun, “malus” meaning evil and “malum” meaning apple. Notably, in the 16th century the eggplant was called “mala insana” (“mad apple”), as well as “poma amoris” (“love apple”), a term also applied to the tomato, all these fruits commingling in language as if what mattered were not their individual characteristics but the sheer glory of fruitiness as a category — the abundance, extravagance, juiciness of the natural world, relentlessly flowering and swelling. Everywhere our ancestors looked, on the tree, vine, shrub, on the plate, there was evidence of life perpetuating itself: fertility incarnate.

Still, the eggplant is a relative newcomer as botanical sex symbols go, perhaps because it is not properly phallic across species; it has been catapulted to stardom only in emoji form. No such confusion surrounds the peach, with its telltale cleft. In China, where the fruit was first domesticated, the phrase “sharing the peach” has long conveyed gay male desire. A story from the third century B.C. recounts how a young man bit into a peach, then handed it to his noble master, who, rather than take this as an insult, understood it as an act of intimacy and sank his teeth into the flesh, too — a theme reprised more explicitly in the Italian director Luca Guadagnino’s 2017 film, “Call Me by Your Name” (adapted from the 2007 novel by the American writer André Aciman). The fruit carried similar freight in early 17th-century Renaissance Italy, as the art and food historian John Varriano has noted, when “dare le pesche” (literally, “to give the peach”) translated as “to yield one’s bum.” In 2016, Apple unveiled a redesigned peach emoji with the cleft delicately pushed to the right, almost out of sight. Users expressed dismay. The cleft was restored to its rightful place.

The banana has a similarly louche aura, which presented something of a challenge to prudish sensibilities when it entered the American imagination after the Civil War. (Steamships had started to replace schooners, shortening travel time from the Caribbean so that fruit wouldn’t rot before arrival.) So obvious was the banana’s shape, etiquette manuals demanded that it be cut with a knife and eaten with a fork rather than raised whole to the lips. One importer felt compelled to print and distribute postcards of women sedately eating bananas, as staid as cows chewing their cud, to show that it was socially and morally acceptable to do so. A century later, the banana would become a handy tool in sex ed classes, as a model on which to demonstrate condom technique. Why, then, has the eggplant deposed the banana as the most phallic of fruits, at least in the digital sphere? One emoji user I consulted suggested that it’s because the emoji version shows the fruit half-peeled — although surely that makes it all the franker, gleefully unzipped. Another noted that the curve of the banana emoji wasn’t quite right, as if realism were the point.

Fantasy instead prevails. The language of food has always veered perilously close to erotica, and the imagery of food to porn, genres that rely heavily on exaggeration, wishful thinking and a willingness to elide unattractive details — to present the world through a Vaseline-smeared lens. It seems unsporting to point out that the banana, for all its jaunty virility, is a fragile thing, a mere clone, incapable of sexual reproduction: a eunuch in the garden. And as a commercial monocrop, it faces an uncertain future. The Gros Michel cultivar, sturdy enough to withstand travel, dominated early international trade, then nearly went extinct in the 1950s, felled by a fungus; now a mutation of that fungus threatens its replacement, the Cavendish, with the same fate. What we take for granted — a blithe joke, a wink — could one day be just a tap on a keyboard.

Some might fear that our dependence on emojis signals a backward step in civilization, a reversion to pictography and the limits of literal representation. But, of course, the eggplant is not an eggplant; it is not even a penis. It is a gesture — lazy, perhaps, but also delightfully multiple in possibility, depending on the person who sends it. It could be a trial balloon, an offhand missive from someone with many eggplants in the fire, or an honest invitation, the tone showboating, triumphant, recklessly hopeful, even numinous. Above all it is silly, as silly as the American glam-metal rockers Warrant yelling for cherry pie in 1990 and the British pop star Harry Styles crooning over watermelon three decades later. Nevertheless, Facebook and Instagram have seen fit, since 2019, to restrict the usage of “contextually specific and commonly sexual emojis” in connection with erotic offers or requests, “because some audiences within our global community may be sensitive to this type of content.” (If only they were as sensitive to political disinformation.) To evade censorship on TikTok, users have taken to deploying the corn emoji as rhyming slang for “porn” (and a phallic object in its own right).

No matter: There is more fruit in the trees. Expand your emojilexicon. Scroll further. Look to the criminally underused mango emoji, No. 542 on Unicode’s list, blushing and sticky sweet, or the buttery, earthy nipple-tipped chestnut, at No. 799. Here, a chile like a cocked eyebrow; there, a split coconut with its flesh so close to cream. Might there be mischief in the kiwi, danger in the tangerine? What lurks under those ruffles of bok choy?

Set Design by Theresa Rivera. Model: Anna Ling at JAG Models. Casting by Studio Bauman.